Each time you start a drama, it’s like a contract between you and the story. The drama says, “If you’re willing to suspend your disbelief and join me for the ride, I’m going to weave a story for you to enjoy.” Then, it’s up to you to decide if you’re going to agree. Are you willing and able to turn off that criticism, and even cynicism, and hop on the magic carpet?

I haven’t met a drama that didn’t ask me to suspend even just a small amount of my disbelief. Sometimes it’s a minor request — there are only moments or instances in the drama that I’ll have to “believe” my way through. Sometimes, though, dramas ask us to suspend a whole lot more of that disbelief, whether it’s a wild premise, or a story that just defies logic and reason. But regardless of how big the ask is, what better give and take is there than to put your inner skeptic on hold and just enjoy?

Enjoyment is actually the reason the suspension of disbelief exists. It’s been a transaction between story (or writer, if you will) and the audience for centuries, but it didn’t become an official term until the 1800s. Here, the Romantic era poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth talked about “the suspension of disbelief” and suggested that if an author’s work had enough “human interest and a semblance of truth” that other more fantastical or unbelievable elements would be forgiven.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because it is the basis for a lot of thoughts around storytelling in general — much like a favorite concept that goes along the lines of: if you have strong and well-drawn characters, the audience/reader will be able to forgive everything else. The argument works for Romantic poetry as much as it works for dear old dramaland. And in a way, dramaland often helps us exercise this disbelief muscle on an episode-by-episode basis.

What are some of the specific ways that dramas require the suspension of disbelief? Well, in the broadest sense, many dramas ask us to accept fantastical or unexplainable plots. A hero playing a cutting edge video game finds that it slowly takes over his reality. A heroine falls in a rain puddle and is transported centuries into the past. An unhappy middle-aged couple wake up one day back in their college heyday, able to make different choices.

It’s pretty easy to suspend disbelief for premises like these, right? They’re given to us upfront as the thesis of our story and we know it’s going to require us to believe something fantastical, supernatural, or metaphysical. We can take it, or leave it. Or perhaps more accurately: believe it, or leave it.

For instance, if you can’t bring yourself to believe that there’s a gate between two very real parallel universes, and that characters can sometimes pass between these worlds, you might find The King: Eternal Monarch a little too far-fetched. If you can’t imagine a world where AI is really able to take on the thoughts, emotions, and persona of a human, A Piece of Your Mind might not be the drama for you.

This idea of accepting a fantastical premise is basically the same argument behind the entire fantasy genre that we know today, and the suspension of disbelief works so effortlessly here (and is so easy for us to accept) because that’s how Coleridge, Wordsworth, and the rest meant it to function. A poem (or K-drama!) might be brimming with wild, gothic elements, but because it’s got enough human interest — i.e., enough emotions and situations that we can relate to — we can in turn accept the fantastical concept.

Today, somewhat unfortunately, the term “the suspension of disbelief” has taken on a more complicated and post-modern meaning. Something more like this: I’m putting my brain on hold to be able to enjoy this story. That’s not only very different from how the concept was originally drawn up, but it’s also a little bit depressing. What if I don’t want to put my brain on hold? Can’t I enjoy a story anyway? There has to be a better way to think about the suspension of disbelief — one that doesn’t make the audience feel like the contract between them and the story means forfeiting logic and reason.

Another term Coleridge used for the suspension of disbelief was “poetic faith,” and I like this a whole lot more. I guess faith sounds better than disbelief — and poetic faith? Who doesn’t want to have that? It sounds like a superpower (and it feels like one sometimes, too). Let’s talk about why poetic faith might be a better way to understand how (and why) we accept unrealistic or implausible elements in stories.

We’ve talked about why it’s so easy to accept entire story concepts that require the suspension of disbelief, but why does that get so much harder when we change the scale? How come a story about time travel is all well and good, but a story where someone just so happens to find an old letter, unearth a random secret in someone’s top drawer, or overhear someone else’s oh-so-crucial conversation, gives us a huge moment of pause?

We, as viewers, are amazingly tough on situations like this. Why is that? It’s because they are circumstances and situations that we can’t easily see happening. They rely on chance (or even deus ex machina), and our brains, reacting from our place of experience with real life, won’t give it a chance. So we baulk.

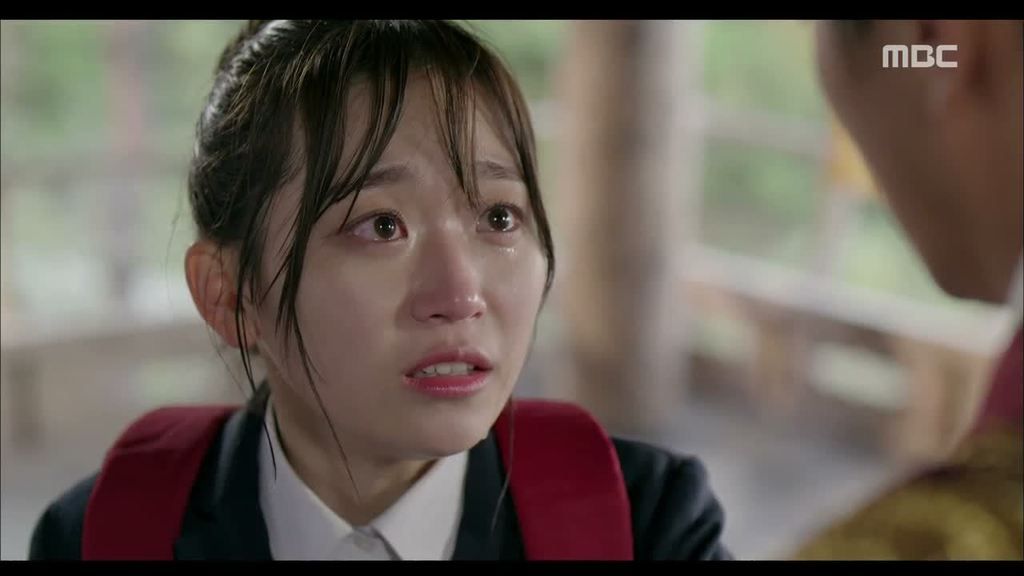

Here’s an example of how that played out for me recently in a scene from When My Love Blooms (it’s a bit long, so buckle up). Our hero is reminiscing on a romantic and treasured memory where he protected his girl from an onslaught of falling books. My brain’s first thought: the chances of a bookshelf in a bookstore collapsing and falling all over the place are pretty slim, but this is a beautiful moment, so I shall momentarily accept that this occurred.

Later, when we revisit the scene, we learn that the heroine, though protected, got a fingertip slammed by one of those books. This resulted in a unique scar on her fingernail. My brain’s next thought? No, that’s not how it works. I’ve injured a fingernail many a time, and seen others do it as well, and what happens is not a pretty little bruise on your nail bed. No, says my brain. You either kill the nail right at the root and it turns black and falls off, eventually growing back, or your nail has a minor mark/injury that grows out in a matter of weeks, since that is what nails do. And just like that, what I’ve witnessed in this scene is rejected by my brain.

Do you see what just happened, though? My rational (okay, semi-rational) brain just took all the beauty and romance (in the capital R sense of romance) in this scene and effectively killed it. Instead, I’m left with a story I don’t trust, and an extremely cynical taste in my mouth. Why did I bother?

This was just one rather minute example, but if you think back to any drama you’ve watched, I’m sure you can come up with a similar situation. It doesn’t have to be a construct for a recognition scene like this nail bruise was (our hero recognizing the masked pianist by that very scar). Instead, it can be a broader part of the story — like the alarming frequency of head/brain injuries in a drama like Chocolate, for instance. In this drama our hero was, of course, a neurosurgeon, so these injuries had to exist around him as a part of his world.

But while these “unbelievable” elements might be implausible, they’re also carefully chosen and built for their stories. Why are we so intent on calling them out, as if we’ll get some sort of prize for being smarter than the story? Maybe what we’re really doing is just killing the magic.

That’s why I like the idea of having poetic faith. And exercising that faith towards the story. Rather than huffing and puffing my way through a drama, I like to remind myself that the story was built that way for a reason: it’s telling a story. That bruise is on a pianist’s fingernail because it enables our hero to recognize his long lost love by her scars — and what a beautiful moment, and metaphor, is that?

Why ruin that moment — and so many others like it — by demanding stories to be just like real life? That’s never been the intention of storytelling. Instead, stories take experiences that we can all relate to, and distill them into something complete, with a beginning, a middle, and an end. If I wanted a drama that was just like everyday life — well, I wouldn’t, because that’s not the purpose.

Perhaps my conclusion is this: yes, dramas sometimes ask us to accept crazy things. But mostly, what they’re really asking is for us to enjoy them. Believe in them when they’re unbelievable. Soak up the serendipity and interconnectedness. Hop on that magic carpet.

That contract between you and the story that we talked about at the opening of this piece — what if that contract was actually a contract romance between you and the story? What if the story was trying to win your heart the whole time, just because? And you know what happens at the end of every contract romance story as well as I do. You fall in love despite yourself, despite the obstacles — and most importantly in this case, despite any flaws in fact or logic.